Rooks are incredibly intelligent birds. They have been documented making and using tools, they are thought to have long memories, and they are often found in myth as birds of prophecy and as symbols of death. There is something preternaturally intriguing about them for sure. When young William Bellman wants to show off his new catapult to his friends, he chooses to shoot a rock at a distant rook, killing it on impact. After admiring the true shot, he and his friends all go home and forget about the dead rook. But the parish, building, clamour, parliament, storytelling, or whatever collective noun you choose, of rooks do not forget their fallen comrade.

Life goes on for William though and he seems to live a good and charmed one at that. He learns his uncle's cloth dyeing textile business. He marries happily and has several children. He is wildly successful, well liked, and intelligent. But then tragedy overtakes him. First some of childhood friends die untimely deaths. Then his wife and all but one of his children succumb to an epidemic. As he lays in the graveyard consumed with grief and worry about his final living child who is clearly dying as well, a mysterious stranger who had appeared at all of the funerals William himself has had to attend over the past few years happens upon him and plants an idea, an opportunity arising out of the ashes of the dead, in William's head. William agrees to this deal and his daughter Dora slowly starts to recover. He stops caring about the dyeing industry and turns his attention to the business of death and mourning, building an enormous monument to the grave, a funerary emporium, death's department store. He creates Bellman and Black, purveyors of all things needed to mourn and to die.

Setterfield has written an unsettling story that is no traditional ghost story. Certainly Bellman is haunted by the death he caused so long ago and the losses he suffers in his own life but there is something more, something subtle, dark, and somber to this tale than just a simple ghost story. Almost half of the novel details the charmed life that William leads, going into detail about the processes in the cloth industry. He seems truly to be "to the good" until his own grief threatens to pull him into the grave that so many of his beloved already inhabit. And then he changes, becoming melancholy, obsessed with death, gloomy, and cold. He is driven to make his new business a success and he does that even as the narrative tension starts to tauten with an ominous unease. As those around him wonder about the shadowy Mr. Black, the reader must wonder too if he in fact exists or is just the tortured image of Bellman's increasingly unsettled mind.

Setterfield skillfully evokes the Victorian sensibility with her writing. Through the characters of William and the mysterious stranger, she offers half hidden and obscured intentions that make the story a degree more menacing than it might be otherwise. The interspersed passages about rooks and the mythology behind them are interesting, especially as they are symbols of memory, and these bits certainly add a creepy fascination to the reading. And yet there is little here to keep the reader turning pages beyond Bellman's torments as few of the other characters are well enough described to hold the reader's attention. Setterfield is a writer who knows how to use and manipulate language beautifully but this novel just doesn't have the fullness of an intriguing story behind it on which to hang those elegant and precise words.

Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy of this book for review.

I did a much better job on the reviews this week. Still a large mountain to climb, but... This meme is hosted by Sheila at

I did a much better job on the reviews this week. Still a large mountain to climb, but... This meme is hosted by Sheila at  This past week's mailbox arrival:

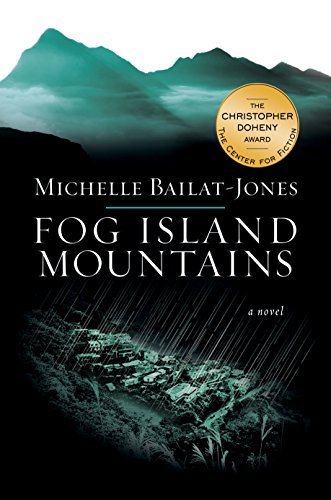

This past week's mailbox arrival: