Emily was 11 years old when her "friends" and classmates labeled her as a slut. Her diary captures her often casual acceptance of this label, the sometime hurt that it caused, and the boy crazy pursuits that it might have inspired. In addition to her diary from the time (names are changed to protect the innocent and the not so innocent), there are sidebars where adult Emily offers commentary on the entries written by her preteen self. The diaries are immature, repetitious, and painful reading. They are full of her crushes and the drama of frenemies. They will make you wince, sometimes with younger Emily and sometimes at younger Emily. The notes by older Emily range from interesting social commentary and expanding on the story she wrote down at the time to completely inane comments about pop culture, fashion, and other nostalgic "gee whiz" moments. The impulse behind writing the book was solid--slut shaming starts early and leaves indelible marks on these young girls--but in practice, the book is pretty cringe-worthy reading. If you want to read someone else's preteen diaries, then this might be the book for you. I can see how some people will be able to overlook the disconcerting format and the lack of real in depth analysis presented here. Me, I remember my own discomfort at that age, and as real and uncensored as Emily's dairies are and as thin as her commentaries are, I didn't learn anything new from them, nor did I really want to spend time in her preteen head, having long since thankfully gotten out of my own.

Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy of this book to review.

It turns out that getting ready to leave for the summer, rally my youngest to get ready too, and leave the house in a reasonable state of being for my husband and oldest (who don't get to bug out of this nasty heat and humidity) cuts into reading and reviewing time terribly! This meme is hosted by Kathryn at

It turns out that getting ready to leave for the summer, rally my youngest to get ready too, and leave the house in a reasonable state of being for my husband and oldest (who don't get to bug out of this nasty heat and humidity) cuts into reading and reviewing time terribly! This meme is hosted by Kathryn at

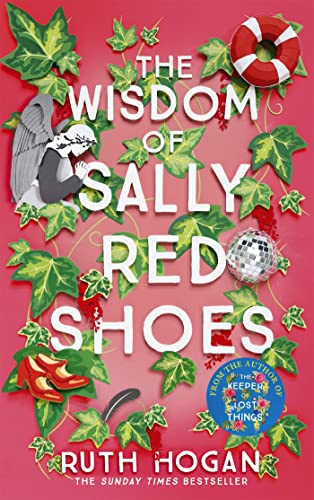

I really should stop indulging myself but I couldn't resist. Can I ever? This past week's mailbox arrival:

I really should stop indulging myself but I couldn't resist. Can I ever? This past week's mailbox arrival: